The outlook darkens

The Bank of England’s August Monetary Policy Report was sobering indeed. Rates were raised 50bp – the biggest rise in 27 years – and the Bank’s headline forecast is for a recession of the scale experienced in the early 1990s. Following a near doubling in gas prices since the Bank’s last report in May, household energy bills are set to rise by 75% in October. This will put energy bills three times higher than a year ago, and push the economy firmly into recession for over a year, on the basis that interest rates follow market expectations and rise to 3% (in May, markets were expecting rates to peak at 2.5%). Inflation is expected to top 13% in Q4 compared with 10% previously.

The Bank of England acknowledges significant uncertainty surrounding the forecast this time, particularly around the outlook for energy prices. Under the Bank’s central forecast where energy prices are assumed to flatline after six months, Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation is still 9.5% in 2023 Q3; if the Bank adjusts their energy price outlook to follow futures curves, CPI inflation is instead 8.4%. Meanwhile, the Bank plan to start Quantitative Tightening in September, selling £80bn of gilts in the first year, adding modestly to the extent of monetary tightening being undertaken.

Why are central banks raising rates now?

There is understandable disagreement over what action the Bank of England should be taking right now. Inflation at multiples of the target for a prolonged period seems to justify rate rises. But the sharp rise in energy prices will slow both the economy and inflation further via the squeeze in consumer and firm buying power. Usually, the Bank would avoid putting up rates during an energy price shock. However, that’s on the basis of the temporary inflation impact not leading to rising wages or rising inflation expectations, and on inflation otherwise being contained. Amidst the economic noise, there are signs of demand outstripping supply in the UK, most prominently in the labour market where we have the lowest number of unemployed people per vacancy on record. Meanwhile, energy accounts for around half the current level of inflation. Arguing that the economy is in-effect overheating and needs higher interest rates while growth evaporates is a hard point to land. The Bank is not alone in facing this dilemma: both the European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve have tightened monetary policy while their respective economies weaken.

How can the government help business weather the winter storms?

We face further stinging rises in energy costs for consumers, which will push the economy into recession. Like monetary policy, fiscal policy has a fine line to walk: easing the hit to demand in the short-term, underpinning growth for the medium term, allowing monetary policy to freely operate so as to cement a hoped-for decline in inflation next year, all while ensuring that public finances are sustainable. A plan to deal with the impact of the October price cap rise needs to be announced urgently.

Key statistics:

- Employment rate (March 2022 – May 2022): 75.9%

- Unemployment (March 2022 – May 2022): 3.8%

- Productivity growth (Output per hour, Q1 2022

on a year ago) -0.8% - Real wage growth (March 2022 – May 2022 on a year ago, excl. bonuses): -2.8%

- CBI growth indicator: +8%

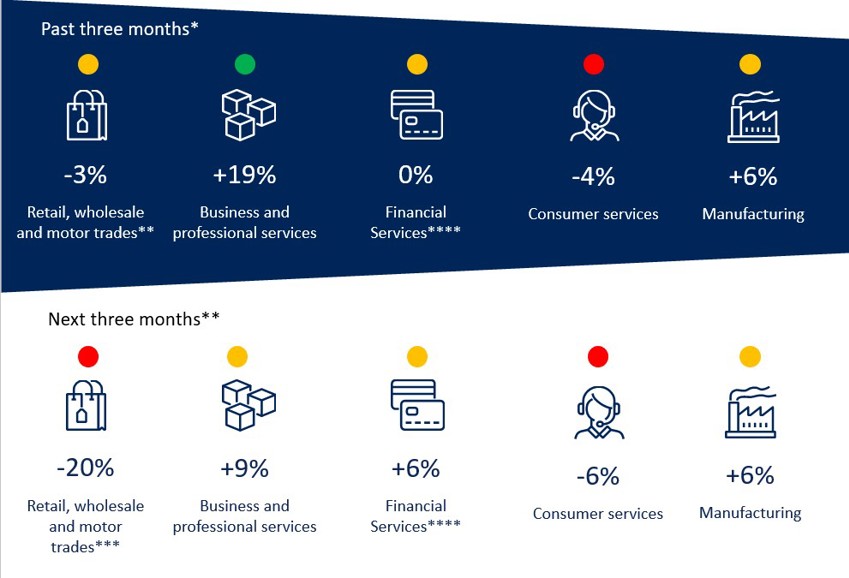

* July surveys were in field between 24 June and 13 July. (not including FSS).

**Figures are percentage balances — i.e. the difference between the % replying ‘up’ and the % replying ‘down’.

*** CBI Growth Indicator uses three-month-on-three-month growth, rather than year-on-year as used in the Distributive Trades Survey

**** Financial services are not included in the growth indicator composite; the latest FSS was June 2022.