The Bank of England (BoE) raised interest rates by 50 basis points last week, to 1.75% – this marked the biggest rise in rates in 27 years, and follows in the footsteps of other central banks implementing outsized rate rises in a bid to tackle inflation. Most notably, the US Federal Reserve has now raised interest rates by 75 basis points twice in a row.

The Bank of England also warned that the economy would enter a recession at the end of this year – read CBI economic analysis to navigate doing business during the oncoming downturn.

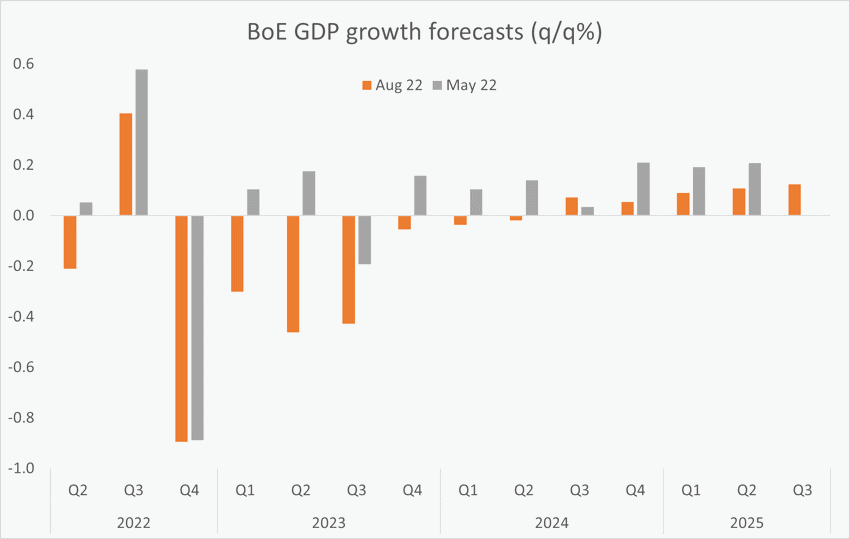

The Bank of England predicts a recession, lasting for over a year.

Click though the topics for key analysis on the months ahead.

Why did the Bank of England raise interest rates again?

The vote for a 50bp rise was almost unanimous. Only one member of the Monetary Policy Committee (Silvana Tenreyro) favoured a smaller rate rise (25 basis points), but acknowledged that a bigger move could be justified too – supported by the worrying forecast from the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) for much higher inflation.

The CPI rate is forecast to peak at an eye-watering 13% at the end of this year – primarily due to a near-doubling of wholesale gas prices since the last forecast in May.

Against this backdrop, the Committee noted that inflationary pressures were becoming more persistent and broadening to more domestically-driven sectors: with a tight labour market and pricing power still reasonably strong, there’s a risk that, despite falling global price pressures, these aren’t enough to bring inflation expectations down.

The Bank actually expect higher inflation to tip the economy into a recession at the end of this year, which persists over 2023. The total fall in output is comparable to that seen during the 1990s recession.

What lies ahead for monetary policy?

The Bank’s forecasts are conditioned on financial markets’ expectations for interest rates. Markets are now expecting the Bank to up rates again, to a peak of 3% in Q2 next year – that’s five more rate rises (each of 25 basis points) in the next six months. Under this assumption, the Bank forecasts that CPI inflation should fall to the 2% target within two years.

Minutes of the MPC’s meeting reiterated that they would “act forcefully” in response to more persistent inflationary pressure if needed – another 50 basis point rise is not off the table.

However, there is no getting away from the fact that the Bank will now be tightening monetary policy into a definitive recession. As such, the growth/inflation trade-off facing them will become trickier to navigate.

Finally, the Bank also set out a plan for selling off its holdings of government bonds (“quantitative tightening”). The pace of asset sales is fairly restrained, amounting to only a further modest tightening in monetary policy.

Spike in gas prices fuels inflation further…

The main development underpinning the Bank’s forecast revisions is a near-doubling of wholesale gas prices since their last forecast, due to Russia restricting the flow of gas to Europe. The Bank now expects a 75% rise in Ofgem’s energy price cap in October – much higher than their previous assumption of 40%. The Bank has also accounted for more frequent changes to the cap (i.e. quarterly rather than bi-annually).

As a result, CPI inflation is now expected to peak at just over 13% in Q4 2022 (vs around 10% previously). Alongside higher gas prices, the Bank also expect stronger domestic inflationary pressure, in part due to predictions of stronger wage growth.

Beyond this year, pressure on inflation is set to ease: as global commodity prices start to normalise and tradable goods inflation falls back. As weak demand leads to more economic slack, domestic price pressures should start to drop – leading to lower inflation expectations.

However, inflation will remain high until early 2024, only returning to the 2% target in Q3 of that year.

…tipping the economy into a recession

The Bank has downgraded their outlook for the economy significantly, now expecting a recession over 2023.

The expected fall in output (around -2.25%) is similar to that seen in the 1990s recession (-2.1%), but lower than that seen over the 2008/9 financial crisis (-5.9%).

But, the Bank assumes no further changes in fiscal policy. So it accounts for the Cost of Living support package announced in May, but does not factor in any potential tax cuts (and the associated boost to growth) from a new government.

Energy price outlook is crucial to economic prospects

The MPC stressed the large degree of uncertainty around their forecasts at present, particularly due to the influence of energy prices, stemming from Russia’s actions around energy supply.

On the outlook for global energy prices, the Bank’s convention is to assume that they move in line with futures curves for six months, and remain unchanged thereafter. However, this means that their assumption for energy prices over the longer-term is much higher than markets are currently predicting.

Under a scenario where energy prices move in line with futures prices throughout the BoE’s forecast (i.e. are lower than assumed), CPI inflation would be 1 percentage point lower this time next year, and 0.5 percentage point lower two years ahead.

While the economy would still fall into a recession, the fall in output would be smaller (-1.5%) than in the Bank’s central forecast (-2.25%). The MPC hinted that they are putting more weight than usual on this scenario.

The MPC also looked at a scenario where domestic inflationary pressures are more persistent – with firms passing on the increases of labour costs via higher prices. GDP would be a little lower under this scenario, but near-term inflation would be significantly higher – by 1.25 percentage points a year ahead, and by 0.75 percentage point in two years time.

The scenarios underscore just how much forces influencing the outlook are outside of the MPC’s control, particularly on the global energy front.

Quantitative tightening (selling holdings of government bonds) set to begin next month

As expected, the MPC also outlined their early plans for selling off its holdings of government bonds under their Asset Purchase Facility – popularly known as “quantitative tightening”. Alongside rising interest rates, this is also another instrument to tighten monetary policy.

The Committee aims to commence gilt sales shortly after their September policy meeting, subject to economic and market conditions. They are aiming to sell £80 billion worth of gilts within the first year, implying a sales programme of around £10 billion per quarter (due to the maturity profile of gilts). The amount sold beyond this would be decided next year, as part of an annual review of gilt sales.

Notably, the MPC agreed that there would be a “high bar” for amending the planned reduction in the stock of gilts outside of the annual review.

The £10bn sell-off of gilts in each quarter is very similar to what we had pencilled into our last forecast, and implies only a very modest tightening in monetary conditions.