Monetary policy authorities struggle to land complex messages

All three central banks across the EU, UK and US have recently increased rates by 75 basis points to bring down soaring inflation amidst weakening growth outlooks. For the Bank of England, this was the biggest rate rise since 1989. For the US Fed, this was the fourth hike in a row and for the ECB, the second. The three economies are operating at different speeds too: in Q3, the US is estimated to have grown 0.6%, the euro area 0.2% (down from 0.8% in Q2) while the BOE expects UK GDP to have shrunk by 0.5% (from growth of 0.2% in Q2).

All three economies have different exposures to the war in Ukraine, pandemic legacies, levels of fiscal support and economic outlooks. It’s no surprise that markets are struggling to digest complex economic shocks, outlooks, and rapidly rising interest rates. Unfortunately, central banks are struggling to communicate their judgements on the outlook too. US Fed watchers were left confused when the central bank said it would be raising rates more slowly but to a higher level. And the Bank’s November Monetary Policy Report spent a lot of time talking about a forecast predicated on an interest rate trajectory with which it fundamentally disagrees.

What does the Bank of England really think?

The Bank of England’s November Monetary Policy Report fuelled widespread reports of the Bank forecasting the longest recession since the 1920s, with output shrinking through to 2024 Q4. Unhelpfully, despite being the Bank’s central forecast, this isn’t what the Bank actually thinks will happen. That forecast was based on market forecasts up to 25 October for an interest rate peak of 5.25%. If interest rates followed that path, inflation would fall below 2% in two years, and fall further beyond that, leaving the Bank in breach of its inflation mandate to return inflation to the 2% target sustainably. The Bank also presented a second forecast in which interest rates stay at 3% throughout their forecast, which also has inflation falling below target in the third year, but has the recession ending in 2023 Q4.

What to make of all this? Elsewhere in its report, the Bank indicates that rates will probably go up a bit further. Both of the Bank’s forecasts have inflation at 5-6% by the end of 2023. And both show a pretty weak growth outlook, with households buffeted by rising energy and mortgage costs, and businesses by tighter financing conditions.

Purse strings tighten for November Budget

Our expectation for the Budget on 17 November is that it will be focussed on reinforcing macroeconomic stability through the demonstration of sound public finance management. This means that a mix of spending cuts and tax rises is expected to help stabilise UK public sector debt. The period of lacklustre growth after the financial crisis is a reminder of the dangers of pushing for too much fiscal consolidation too soon. But debt repayments are far higher now as financing costs have gone up and so has the level of debt, and markets are anxious. A delicate balance of affordable support for businesses and households through the energy crisis in the short-term (in a way which doesn’t complicate the Bank’s inflation task) and growth-friendly fiscal consolidation in the long-term, is needed.

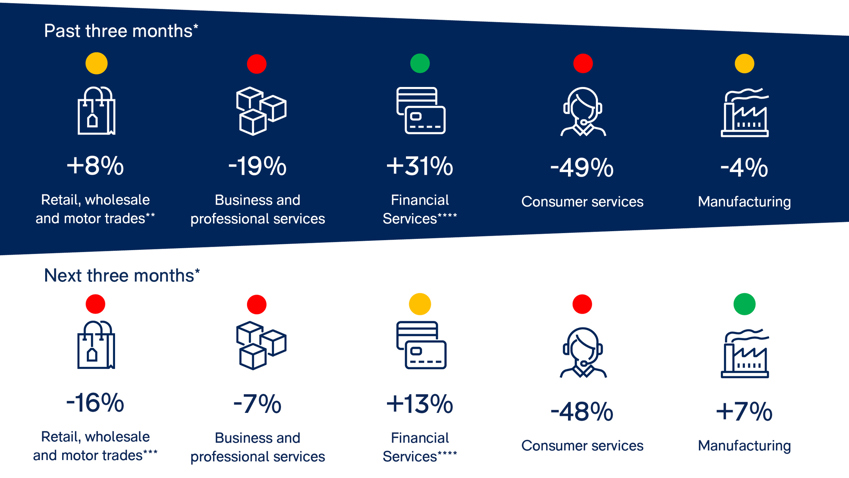

The picture in key sectors of the UK economy

* August surveys were in field between 26 July and 15 August. (not including FSS).

** Figures are percentage balances - i.e. the difference between the % replying ‘up’ and the % replying ‘down’.

*** CBI Growth Indicator uses three-month-on-three-month growth, rather than year-on-year as used in the Distributive Trades Survey

**** Financial services are not included in the growth indicator composite; the latest FSS was June 2022.